As we board our ship, the people we see today are us.

We are almost all within about 15 years of age – 65 to 80. We are all within about 15 years of our retirements. We are all quite fit, with only a few having mobility problems. We are all nicely, but not formally, dressed. We are almost all Caucasian. There are two mixed racial couples, one of them two men, apparently gay. There are twelve other Canadians and two Brits on board diluted among the 186 passengers. All the rest are Americans. Almost all department heads and most of the crew were from Romania. Our cruise director, Richie Lee seen here on the left, is from Wales. We never hear a language on board other than English.

For our American fellow travellers, most seem to be Democrats. This is important given the highly polarized political situation in the U.S.A. We travel together as the impeachment storm is brewing around Trump. There may be some Republicans on board but we are afraid to ask and maybe they are careful about letting their perspective be known.

We have all retired from professional and semi-professional occupations: nurses, at least one dentist and one attorney, and one university professor, business owners and civil servants too. Teachers seem somewhat over represented, which makes sense because the focus of the cruise is on learning about culture and history. Most of us have grandchildren, but not too many.

Today and for the next two weeks on the Viking Longship Gefjon (pronounced with a hard ‘g” and the ‘j’ as if it were a ‘y’), we are us. Oh and by the way, the photo above is our Gefjon docked in Budapest right at the famous chain bridge.

We are almost all within about 15 years of age – 65 to 80. We are all within about 15 years of our retirements. We are all quite fit, with only a few having mobility problems. We are all nicely, but not formally, dressed. We are almost all Caucasian. There are two mixed racial couples, one of them two men, apparently gay. There are twelve other Canadians and two Brits on board diluted among the 186 passengers. All the rest are Americans. Almost all department heads and most of the crew were from Romania. Our cruise director, Richie Lee seen here on the left, is from Wales. We never hear a language on board other than English.

For our American fellow travellers, most seem to be Democrats. This is important given the highly polarized political situation in the U.S.A. We travel together as the impeachment storm is brewing around Trump. There may be some Republicans on board but we are afraid to ask and maybe they are careful about letting their perspective be known.

We have all retired from professional and semi-professional occupations: nurses, at least one dentist and one attorney, and one university professor, business owners and civil servants too. Teachers seem somewhat over represented, which makes sense because the focus of the cruise is on learning about culture and history. Most of us have grandchildren, but not too many.

Today and for the next two weeks on the Viking Longship Gefjon (pronounced with a hard ‘g” and the ‘j’ as if it were a ‘y’), we are us. Oh and by the way, the photo above is our Gefjon docked in Budapest right at the famous chain bridge.

BUDAPEST — Three men and a chain bridge

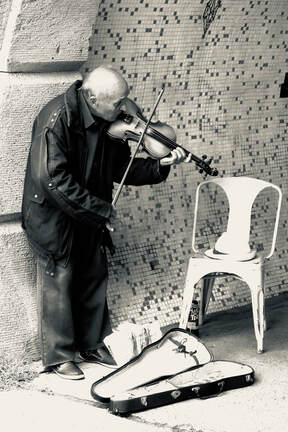

The bridge connects Buda with Pest (pronounced ‘pesht’). One of these men plays violin in an archway beneath the bridge on the Pest side. In exchange for taking his picture, I throw a 2 Euro coin into his violin case.

The second man works the bridge, back and forth. We see him each time we cross, bent over a cane, shuffling along. He shakes a small paper coffee cup with coins in it, looking up at us from his stooped posture with hopeful eyes, his eye contact unabashed. He looks to be two or three decades younger than the violinist. Perhaps some tragedy or injury has befallen him, a back injury I imagine, keeping him from his manual trade. I don’t stop to ask, eschewing the transient obligation to add to his few coins.

The third man is tall, thin. His back is straight, his bearing purposeful, his pace rapid. Brushing past, he bumps my shoulder. I think he is a pick-pocket. Likely not, but it is my thought. He doesn’t stop to apologize or engage me in that brief and awkward fashion that would have made me his mark.

Three men. I was afraid of the last, needlessly. I was touched by the first, he had a look of mournfulness, perhaps the remnant pain of the political regime that once held his country. And the on in the middle? I cannot shake his image from my mind. His pleading eyes and the social strictures I brought with me, draw me back over and over again. I wish now I had added to the rattle in his small paper coffee cup.

The second man works the bridge, back and forth. We see him each time we cross, bent over a cane, shuffling along. He shakes a small paper coffee cup with coins in it, looking up at us from his stooped posture with hopeful eyes, his eye contact unabashed. He looks to be two or three decades younger than the violinist. Perhaps some tragedy or injury has befallen him, a back injury I imagine, keeping him from his manual trade. I don’t stop to ask, eschewing the transient obligation to add to his few coins.

The third man is tall, thin. His back is straight, his bearing purposeful, his pace rapid. Brushing past, he bumps my shoulder. I think he is a pick-pocket. Likely not, but it is my thought. He doesn’t stop to apologize or engage me in that brief and awkward fashion that would have made me his mark.

Three men. I was afraid of the last, needlessly. I was touched by the first, he had a look of mournfulness, perhaps the remnant pain of the political regime that once held his country. And the on in the middle? I cannot shake his image from my mind. His pleading eyes and the social strictures I brought with me, draw me back over and over again. I wish now I had added to the rattle in his small paper coffee cup.

You're on vacation now.

We transferred flights twice to get to Budapest, first in Toronto and then in Amsterdam. Sadly, our luggage didn't make it across the Atlantic. Panicky, and travel weary we arrived at the reception desk on the Gefjon to share the worry of our problem. The Viking representative told us that it was no longer our problem but hers. We were on vacation now! With an offer to launder our travel clothes and with a gift basket of toiletry items left in our stateroom we could begin to enjoy. All that day, and the next, and the next the Viking representative was on the phone with the airline finally managing to have our luggage flown onto to Vienna to be delivered to our ship there. What an introduction to the world of Viking service!

VIENNA

The vistas around St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna all seem vertical. The tops of buildings, particularly the Gothic Cathedral, recede toward a vanishing point in the heavens. This the photographer’s chagrin.

When we arrive in front of St. Stephen’s our heads are already full. We had entered at an ancient city gate and walked past the Hofburg Palace, the centre of the Habsburg Empire. Our guide tunnels hundreds of years of history through our ear-pieces as we walk the crowded sidewalks, clearing the way for bicycles and delivery vans. We are captivated by the story of Maria Teresa who was responsible for expanding the Empire by having 16 children. The ten who survived were strategically married off to secure political ties throughout much of Europe.

Vienna is one busy city. Streets are curved and buildings rise three, four, five or more storeys. Then the narrow streets give way to a broad town square. It is packed. The sun is hot. Soon we escape the common bedlam and find narrow streets and alleys. They are shaded and cool. Tiny shops appear. There is occasional greenery.

Capturing the majesty of the vertical landscape seems impossible. Then two images appear: a horse drawn carriage for the tourists, and bicycles chained to the sidewalk railing for the locals. I am grounded again.

When we arrive in front of St. Stephen’s our heads are already full. We had entered at an ancient city gate and walked past the Hofburg Palace, the centre of the Habsburg Empire. Our guide tunnels hundreds of years of history through our ear-pieces as we walk the crowded sidewalks, clearing the way for bicycles and delivery vans. We are captivated by the story of Maria Teresa who was responsible for expanding the Empire by having 16 children. The ten who survived were strategically married off to secure political ties throughout much of Europe.

Vienna is one busy city. Streets are curved and buildings rise three, four, five or more storeys. Then the narrow streets give way to a broad town square. It is packed. The sun is hot. Soon we escape the common bedlam and find narrow streets and alleys. They are shaded and cool. Tiny shops appear. There is occasional greenery.

Capturing the majesty of the vertical landscape seems impossible. Then two images appear: a horse drawn carriage for the tourists, and bicycles chained to the sidewalk railing for the locals. I am grounded again.

WACHUA VALLEY

Here you see our sister ship, Viking Vilhjalm, passing us on the spacious and deep waterway of the Danube in the Wachau Valley. Upstream the Danube proves more treacherous for our journey.

Water levels on rivers vary. For a river cruise they can be too high, reducing the space between the top of the ship and the underside of the bridges. Such is the case for several days of our journey. Viking Longships are designed to manage this. The railings and awnings of the sun deck are pivoted to lie flat. Even the wheelhouse is lowered so that the height of the ship can pass under the bridge. Despite the low clearance, our ship always gets through.

Low water levels pose another risk: insufficient draft for the ship to pass. An email warned us days before our trip there was a danger this would happen to us. The ship we were to board, the Viking Ve, hadn’t made it down to Budapest. Because of this, we sail on the Viking Gefjon already there. More about our low autumn river levels to come later in this blog.

As we sailed the upper Danube River through the Wachua Valley we caught our first glimpses of European River Castles.

Water levels on rivers vary. For a river cruise they can be too high, reducing the space between the top of the ship and the underside of the bridges. Such is the case for several days of our journey. Viking Longships are designed to manage this. The railings and awnings of the sun deck are pivoted to lie flat. Even the wheelhouse is lowered so that the height of the ship can pass under the bridge. Despite the low clearance, our ship always gets through.

Low water levels pose another risk: insufficient draft for the ship to pass. An email warned us days before our trip there was a danger this would happen to us. The ship we were to board, the Viking Ve, hadn’t made it down to Budapest. Because of this, we sail on the Viking Gefjon already there. More about our low autumn river levels to come later in this blog.

As we sailed the upper Danube River through the Wachua Valley we caught our first glimpses of European River Castles.

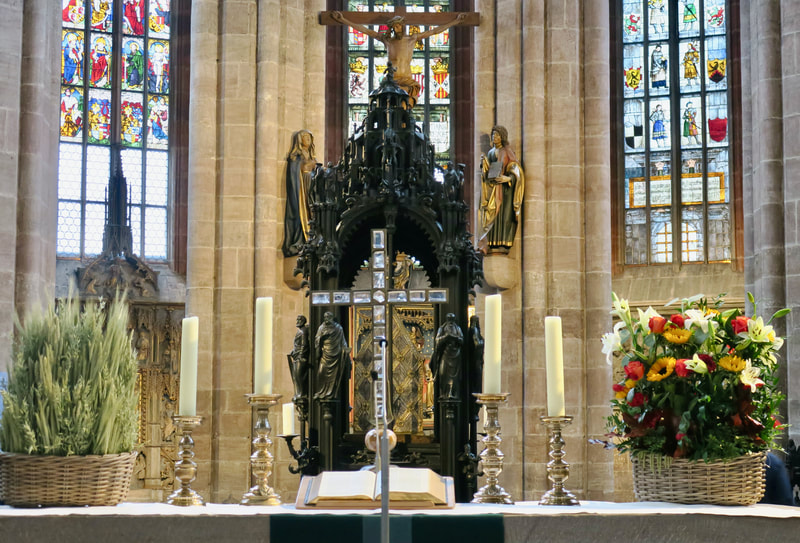

MELK ABBEY

PASSAU

Those scary river levels

At Passau two other rivers join the Danube – the Inn and the Ilz. We see the different colours of water flowing in, raising the level of the Danube behind us. Now as we proceed further upstream on the Danube toward its source, water levels are lower. Low water levels may require us to leave the Gefjon and travel by bus from Passau to board a different ship in Regensburg. A ship swap. Our suitcases would be delivered into our exact same stateroom on the next ship. The bus journey is about 90 minutes.

The night before our docking in Passau, a grim cruise director, Rickie Lee, announces that this daily “port talk” requires that at least one person from each stateroom attend. Presumably, this means that there would be a ship swap. He greets us equally as grimly, reminding us that we had been advised about variable river levels and what it might mean for our cruise.

We have been graced with the best of service by the crew of the Gefjon. A ship swap means we would leave them behind. Sadness falls over us.

Of course, our Richie Lee is quite an actor. He manipulated us into believing in this inevitable, so he could then announce that we wouldn’t have to leave our crew behind, that rains had raised the water level sufficiently for us to get through. Cheers ring out. We've been collectively had, but are so delighted with the good news.

The night before our docking in Passau, a grim cruise director, Rickie Lee, announces that this daily “port talk” requires that at least one person from each stateroom attend. Presumably, this means that there would be a ship swap. He greets us equally as grimly, reminding us that we had been advised about variable river levels and what it might mean for our cruise.

We have been graced with the best of service by the crew of the Gefjon. A ship swap means we would leave them behind. Sadness falls over us.

Of course, our Richie Lee is quite an actor. He manipulated us into believing in this inevitable, so he could then announce that we wouldn’t have to leave our crew behind, that rains had raised the water level sufficiently for us to get through. Cheers ring out. We've been collectively had, but are so delighted with the good news.

REGENSBURG

In Regensburg I stand beside a wall built by the Romans nearly 2000 years ago. Originally a garrison for a legion of Roman soldiers, this place has been continuously inhabited for two millennia. A bridge astride the Danube came 1100 years later; of course, it is still ancient by any standard. Cobblestone streets were added later yet, a defense against the mud.

Yet it still feels gritty somehow. Real. Perhaps it’s the light, but the walls don’t seem as pastel pure as those of Passau the day before. The air of the day pushes us a chill, the clouds seem to hang lower.

Tour groups trip over each other, speaking their commentaries into ear pieces. 2000 years of history distilled into 90 minutes, one old building after another. In the pedestrian streets we dodge cars, delivery vans and the ubiquitous bicycles.

I had stolen into the city early in the day to catch the streets free of tourists. I found some bicycles, each awaiting a particular human, chained to walls on ancient streets and alleys. And I must remember, people live here and need to get around. Not all of us are on vacation with our needs provided.

Yet it still feels gritty somehow. Real. Perhaps it’s the light, but the walls don’t seem as pastel pure as those of Passau the day before. The air of the day pushes us a chill, the clouds seem to hang lower.

Tour groups trip over each other, speaking their commentaries into ear pieces. 2000 years of history distilled into 90 minutes, one old building after another. In the pedestrian streets we dodge cars, delivery vans and the ubiquitous bicycles.

I had stolen into the city early in the day to catch the streets free of tourists. I found some bicycles, each awaiting a particular human, chained to walls on ancient streets and alleys. And I must remember, people live here and need to get around. Not all of us are on vacation with our needs provided.

NUREMBURG

A series of defensive structures safeguard the castle.

The zig-zag of bastions and a dry moat precede the city wall. The castle sits just inside. A long, winding ramp leads to the gate. Deterrents have guaranteed that this castle, and the medieval city also within the wall, would never be taken. It never was.

Nuremburg.

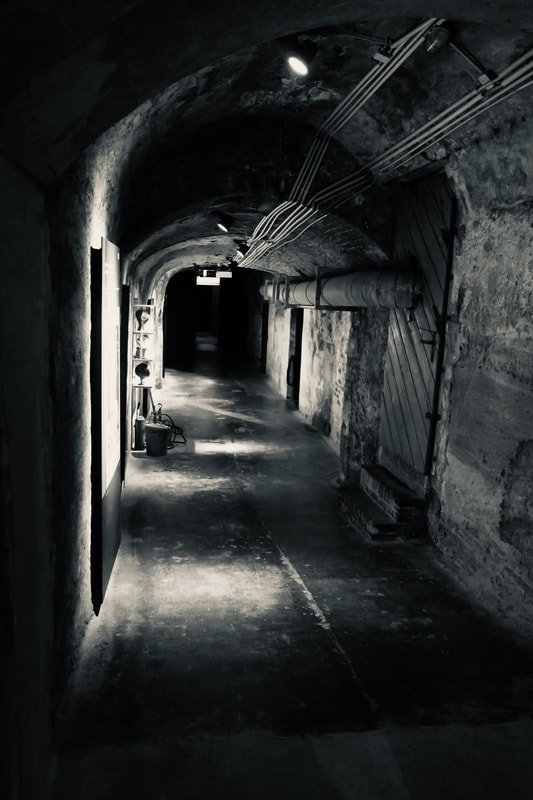

Underground bunkers lie beneath the castle, created to store beer. Art and antiquities were stowed in those bunkers during the Second World War. While the city walls, bastions and moats could not protect the city against the aerial bombing of January 1945, beer bunkers re-engineered to guarantee optimal temperature and humidity would safeguard its treasures.

The German guide who takes us there speaks non-defensively, factually relating the horror of war in this most German of German cities. He accepts the role Germany played in inciting the mutual destruction of cities on either side of the channel. In his voice I hear shame and anger at what was wrought. Emotion clutches his voice as he translates recordings of speeches by Hitler and Goebbels played in all their crackling horror over a speaker for us to hear. He speaks of the demoralizing effect Goebbels’ words would have had on the people who had just seen 90% of their historic city destroyed. His carefully chosen words urge us to learn from this horrendous past.

But the story doesn’t end there. On the same medieval street grid, Nuremburg is reconstructed. Care is taken to replace destroyed buildings with new ones of the same dimensions and roof lines. It takes decades. Today, it looks much the same as before the bombing.

Sculptures of the Madonna and Christ Child retrieved from the bunkers adorn the corners of buildings again.

They are placed there to protect those who live within.

The zig-zag of bastions and a dry moat precede the city wall. The castle sits just inside. A long, winding ramp leads to the gate. Deterrents have guaranteed that this castle, and the medieval city also within the wall, would never be taken. It never was.

Nuremburg.

Underground bunkers lie beneath the castle, created to store beer. Art and antiquities were stowed in those bunkers during the Second World War. While the city walls, bastions and moats could not protect the city against the aerial bombing of January 1945, beer bunkers re-engineered to guarantee optimal temperature and humidity would safeguard its treasures.

The German guide who takes us there speaks non-defensively, factually relating the horror of war in this most German of German cities. He accepts the role Germany played in inciting the mutual destruction of cities on either side of the channel. In his voice I hear shame and anger at what was wrought. Emotion clutches his voice as he translates recordings of speeches by Hitler and Goebbels played in all their crackling horror over a speaker for us to hear. He speaks of the demoralizing effect Goebbels’ words would have had on the people who had just seen 90% of their historic city destroyed. His carefully chosen words urge us to learn from this horrendous past.

But the story doesn’t end there. On the same medieval street grid, Nuremburg is reconstructed. Care is taken to replace destroyed buildings with new ones of the same dimensions and roof lines. It takes decades. Today, it looks much the same as before the bombing.

Sculptures of the Madonna and Christ Child retrieved from the bunkers adorn the corners of buildings again.

They are placed there to protect those who live within.

BAMBURG

This medieval city of Bamburg sustained very little bomb damage in WWII and so we see the actual half-timber buildings, three and four storeys high, many with sandstone facades, all with steep tile roofs. Some have cheerfully painted stucco walls, window boxes still in flowers despite our October visit, and painted shutters. Cobblestone streets that once echoed the hoof sounds of horses now bear small cars, snaking through their tangle.

I walk those streets too, walk them in a clot of tourists that could block a narrow street. We hear the commentary of a university student who is majoring in sociology but has an interest in history. In addition to the requisite 1000 years of religion, politics and prejudice, we hear of an abattoir that polluted the river, beer that tastes like bacon and historically why that is so, and a town hall that was diplomatically built in the river between the Island Town and the Hill Town. A fresco embellishes the side of the building. The artist’s leg still pokes provocatively through the base of that fresco. The cupid points to the signature of the artist. These and other historical oddities give character to the place.

I walk seeing students on bicycles, a class of young children, and dogs on leashes. My partner comments that there are many shops with children’s things in them. As much history as is here, it needs its future too.

And just a comment on the photos of two external cathedral statues shown below. The one on the left was described as a example of pre-literate anti-semitism. As worshipers came into the cathedral they viewed the depiction of a Jewish woman, blindfolded to the truth of Christianity, the tablets of the law slipping from her hand. And on the right below? Well, that's just an angel playing some really cool jazz! Imagine. I think he should get together with the cupid playing heavy metal guitar you can see in the picture from Nuremburg up above.

So a story from Bamburg ...

He walks his bicycle, his right hand steady in the centre of the handlebars. She pushes a stroller, the kind big enough to comfortably fit a toddler. His left hand steadies a baby who rides on his shoulders. The baby looks to be very young, just old enough to hold her head securely. His hand never leaves the child.

They walk streets below the Bishop's Residence in Bamberg - the Bishops New Residence actually, the one that is only 400 years old. Its rose garden is formal and austere on the hill above the medieval streets below.

Follow the eye in the map below. The street directly in front of the eye is the same street at the bottom of the photo in the middle (this photo was taken from the rose garden in the Bishop’s New Residence on the hill above). This street is near where I see the young family walking.

They walk streets below the Bishop's Residence in Bamberg - the Bishops New Residence actually, the one that is only 400 years old. Its rose garden is formal and austere on the hill above the medieval streets below.

Follow the eye in the map below. The street directly in front of the eye is the same street at the bottom of the photo in the middle (this photo was taken from the rose garden in the Bishop’s New Residence on the hill above). This street is near where I see the young family walking.

WURZBURG

So, here is how the story goes.

Medieval Wurzburg generates much wealth on the east-west trading route of the Main River (“Main" is pronounced like “mine", with an elongated ei vowel). Among noble families, certain males are designated to become priests. With sufficient funds a Priest from a Noble family can win the favour of the Pope to rise to the status of Bishop. It is both a political and clerical role, a seat of power and wealth. In the early 18th Century the Bishop, dissatisfied with the Fortress Castle atop the hill overlooking the river and town, decides to have built for his celibate self a residence. A palace of 350 rooms will do.

It takes 25 years to build. From griffins to gold leaf, from innovations in painting and stucco which create three dimensional realism to tapestries and mirrored surfaces, from the red carpeted staircase to the marble floors to the domed ceilings, the opulence ascends. A garden in the style of Versailles graces the grounds. We weren't allowed to take pictures inside, I think so they could sell postcards of the grandiose interior.

It all seems so distant, beautiful, but distant. It is distant in time and privilege: a style of wealth and a way of life that is beyond today’s imagination.

But this is not the only Wurzburg I found. Before the tour that took me through the Palace, I walked the early morning streets.

I linger on the ancient bridge. The fortress castle stands hundreds of feet above guards it, the pilgrimage church prays for it, autumn leaves grace it with one last riot of colour before they descend into winter’s grey.

This is a city where people, ordinary people like me, cross an ancient bridge on the way to their day. Mothers push strollers, adults of all ages ride bicycles. Streams of traffic dutifully stop at stoplights and pedestrian crossings. Streetcars are hung from electrical lines. An empty bottle of vodka is perched on the concrete steps beside the river, perhaps purchased the night before from the motorized sidewalk liquor cart parked not too far away. Park benches go unoccupied, the seats wet from last night’s rain. There's a blank expression on the face of a man on the streetcar; another man carries the front tire of his bike home from the repair shop so he can make his way to work. Life is lived quite differently from that opulent Bishop of 250 years before.

Medieval Wurzburg generates much wealth on the east-west trading route of the Main River (“Main" is pronounced like “mine", with an elongated ei vowel). Among noble families, certain males are designated to become priests. With sufficient funds a Priest from a Noble family can win the favour of the Pope to rise to the status of Bishop. It is both a political and clerical role, a seat of power and wealth. In the early 18th Century the Bishop, dissatisfied with the Fortress Castle atop the hill overlooking the river and town, decides to have built for his celibate self a residence. A palace of 350 rooms will do.

It takes 25 years to build. From griffins to gold leaf, from innovations in painting and stucco which create three dimensional realism to tapestries and mirrored surfaces, from the red carpeted staircase to the marble floors to the domed ceilings, the opulence ascends. A garden in the style of Versailles graces the grounds. We weren't allowed to take pictures inside, I think so they could sell postcards of the grandiose interior.

It all seems so distant, beautiful, but distant. It is distant in time and privilege: a style of wealth and a way of life that is beyond today’s imagination.

But this is not the only Wurzburg I found. Before the tour that took me through the Palace, I walked the early morning streets.

I linger on the ancient bridge. The fortress castle stands hundreds of feet above guards it, the pilgrimage church prays for it, autumn leaves grace it with one last riot of colour before they descend into winter’s grey.

This is a city where people, ordinary people like me, cross an ancient bridge on the way to their day. Mothers push strollers, adults of all ages ride bicycles. Streams of traffic dutifully stop at stoplights and pedestrian crossings. Streetcars are hung from electrical lines. An empty bottle of vodka is perched on the concrete steps beside the river, perhaps purchased the night before from the motorized sidewalk liquor cart parked not too far away. Park benches go unoccupied, the seats wet from last night’s rain. There's a blank expression on the face of a man on the streetcar; another man carries the front tire of his bike home from the repair shop so he can make his way to work. Life is lived quite differently from that opulent Bishop of 250 years before.

WERTHEIM

Wertheim is a delightful town with a cozy town square of half-timber buildings. All the shops are owned by local proprietors. A street vendor sells me an awesome Bratwurst on a bun with German sweet mustard. A gifted glass blower with a great business model provides gorgeous, graceful souvenirs for us to buy as memories of the town. I can even get a pair of riding gloves for the afternoon bike ride along the Main.

The town of Wertheim is on the Main River The medieval town centre is about six feet above the river level on the day we dock there.

That bit is important, the estimate about how high the town is above the river level, because…Wertheim floods.

Now in North American cities, if there is a flood, it is a disaster. Apparently, not so for the citizens of Wertheim. They carry on. The Pointed Tower near the river has developed a lean to one side as a result of 800 years of flooding. That’s okay, it’s still standing and it has been propped up better in recent years so it won’t lean any further.

Our tour guide, a young woman resident of Wertheim, cheerfully tells us of the resilience of the people of Wertheim when it comes to flooding. She stories us with a sly sense of humour, a touch of the naïve, a fetching sparkle in her eye. Townsfolk expect the floods, even have ways of coping with them because they happen so often. The next flood is overdue – there hasn’t been one since 2011 and it has been happening every six years or so. Townsfolk get a warning when it will come and how high it will be. They move everything up to the second floor.

She says there is one plan of action if the water rises less that 17 feet, and a different one if it rises higher. You got that right, 17 feet. Apparently, below 17 feet building owners put barricades to prevent the water coming in. Above 17 feet, well… the water pressure is too great on the ancient buildings. Their foundations are better preserved by letting the weight of the water equalize inside and out.

She shows us pictures. One is of a friendly chat between two residents standing in water up past their knees. The fire department is in another attending to residents in their homes with a boat, helping them with such day-to-day needs such as getting to the doctor or taking the dog for a walk.

It is all quite matter of fact. It happens. They cope.

When I took the accompanying picture I did so for the brave October presence of green leaves and red flowers. Now I see it is about something very different. Up the right side of the picture, etched into the painted column, are the heights of the floods over several years. They do that here and in other river cities. It is a way of saying, floods happen but we are still here. But I bet this picture is missing a few, ones too high on the column to show in the picture. You know, those floods over that 17 feet.

The town of Wertheim is on the Main River The medieval town centre is about six feet above the river level on the day we dock there.

That bit is important, the estimate about how high the town is above the river level, because…Wertheim floods.

Now in North American cities, if there is a flood, it is a disaster. Apparently, not so for the citizens of Wertheim. They carry on. The Pointed Tower near the river has developed a lean to one side as a result of 800 years of flooding. That’s okay, it’s still standing and it has been propped up better in recent years so it won’t lean any further.

Our tour guide, a young woman resident of Wertheim, cheerfully tells us of the resilience of the people of Wertheim when it comes to flooding. She stories us with a sly sense of humour, a touch of the naïve, a fetching sparkle in her eye. Townsfolk expect the floods, even have ways of coping with them because they happen so often. The next flood is overdue – there hasn’t been one since 2011 and it has been happening every six years or so. Townsfolk get a warning when it will come and how high it will be. They move everything up to the second floor.

She says there is one plan of action if the water rises less that 17 feet, and a different one if it rises higher. You got that right, 17 feet. Apparently, below 17 feet building owners put barricades to prevent the water coming in. Above 17 feet, well… the water pressure is too great on the ancient buildings. Their foundations are better preserved by letting the weight of the water equalize inside and out.

She shows us pictures. One is of a friendly chat between two residents standing in water up past their knees. The fire department is in another attending to residents in their homes with a boat, helping them with such day-to-day needs such as getting to the doctor or taking the dog for a walk.

It is all quite matter of fact. It happens. They cope.

When I took the accompanying picture I did so for the brave October presence of green leaves and red flowers. Now I see it is about something very different. Up the right side of the picture, etched into the painted column, are the heights of the floods over several years. They do that here and in other river cities. It is a way of saying, floods happen but we are still here. But I bet this picture is missing a few, ones too high on the column to show in the picture. You know, those floods over that 17 feet.

Feeling much like a senior citizen on a granny bike, I enjoyed the 16 mile ride alongside of the Main River. Despite stopping at a pub, the group beat the Gefjon to the meeting point downstream.

Hey, get used to it, Terry. You are a senior citizen now.

Hey, get used to it, Terry. You are a senior citizen now.

THE UPPER RHINE

Along the middle Rhine Valley, a succession of 40 castles - one after the other, both sides of the river. While some castles are in ruins, many others have been restored to be used as hotels or hostels, privately owned now.

So what would be the story at the narrowest, most treacherous bend in the Middle Rhine?

The Legend of Lorelei.

A 400 ft cliff. The haunting voice of a mermaid pierces through the fog. Sailors are captivated by the beauty as they make their way upstream. If they go off the boat searching for the magical voice they fall to their death from the steep cliff. If they stay on board searching for the origin of the sound, their boats end up fractured onto the rocks in the swift current.

And the Rhine is defended, not by castles, but by song.

The Legend of Lorelei.

A 400 ft cliff. The haunting voice of a mermaid pierces through the fog. Sailors are captivated by the beauty as they make their way upstream. If they go off the boat searching for the magical voice they fall to their death from the steep cliff. If they stay on board searching for the origin of the sound, their boats end up fractured onto the rocks in the swift current.

And the Rhine is defended, not by castles, but by song.

MARKSBURG CASTLE

Part way up to the entrance of the Marksburg Castle we assemble in a martialing area. Here we await the guides with their commentary to bring this castle to life.

We have plodded up the 100 step stairway through the woods. We have yet to pass through the castle door. Beyond that, we will gingerly pick our way through the rocky corridor more fit for medieval horses than for 21st Century humans. On a small landing, we mull about, get our headsets connected, muse together.

Just over our heads, beside a passageway we have yet to enter, there’s a slit in the castle wall. If I was an invader several hundred years ago who happened to have made it thus far, there would be an archer on the other side of that slit ready to… well, let’s not think of that.

Today, through the slit, I see a round face gaze back at me. A child, a boy, he looks to be 8ish or so. First he flashes a smile, then his eyes flit off and a puzzled look comes to his face.

8 year old boys can be fanatical about castles, about knights, about archers. Perhaps as that 8 year old boy looks through that slit there is not a river cruise boat going by, but a fighting ship with the enemy. As he scans the small yard below where I stand, he sees not a buzz of recently retired with bad knees but a sword fight underway.

Maybe he has the best view of all.

We have plodded up the 100 step stairway through the woods. We have yet to pass through the castle door. Beyond that, we will gingerly pick our way through the rocky corridor more fit for medieval horses than for 21st Century humans. On a small landing, we mull about, get our headsets connected, muse together.

Just over our heads, beside a passageway we have yet to enter, there’s a slit in the castle wall. If I was an invader several hundred years ago who happened to have made it thus far, there would be an archer on the other side of that slit ready to… well, let’s not think of that.

Today, through the slit, I see a round face gaze back at me. A child, a boy, he looks to be 8ish or so. First he flashes a smile, then his eyes flit off and a puzzled look comes to his face.

8 year old boys can be fanatical about castles, about knights, about archers. Perhaps as that 8 year old boy looks through that slit there is not a river cruise boat going by, but a fighting ship with the enemy. As he scans the small yard below where I stand, he sees not a buzz of recently retired with bad knees but a sword fight underway.

Maybe he has the best view of all.

COLOGNE

As I step into the cathedral the cacophony of church bells softens. Sunday mass is soon to begin. Those to partake hurry past the tourist folk to find a seat. Votive candles are lit and prayers are whispered in the narthex.

I have never heard church bells like this. Outside, in their call for worshipers, bells vie against each other - sound somersaulting, vaulting over sound – capturing me, overwhelming me. Then I enter. Inside the cathedral the bells hold me gently. No longer beckoning, the bells now engulf, comfort. An audible hug. Small and insignificant in this stone resonance chamber, I listen. My thoughts form again. The rhythm and the dissonance, the discordance of peal upon peal, these are just hushes now, not hurries.

Three quarters of a century ago the sound would’ve been so different. 84 bombs from the RAF hit the Cologne Cathedral. I imagine the hurry to safety as the city is bombed, eventually 95% of it is destroyed. And, that same hurry takes out stained glass windows for safe storage, gets valuable icons to a new place of sanctuary. And then later the hush, the hush of walking the floor of the cathedral then littered with rubble. The hush of devastation, and in seeing the walls of the cathedral still standing, the hush of hope.

I emerge again, leaving the worshippers to their sacred duty. Outside the amplified voice of an announcer throws the names of marathon runners off the gothic façade of the cathedral. Power scooters bump their way over cobblestones. This city is running again.

I have never heard church bells like this. Outside, in their call for worshipers, bells vie against each other - sound somersaulting, vaulting over sound – capturing me, overwhelming me. Then I enter. Inside the cathedral the bells hold me gently. No longer beckoning, the bells now engulf, comfort. An audible hug. Small and insignificant in this stone resonance chamber, I listen. My thoughts form again. The rhythm and the dissonance, the discordance of peal upon peal, these are just hushes now, not hurries.

Three quarters of a century ago the sound would’ve been so different. 84 bombs from the RAF hit the Cologne Cathedral. I imagine the hurry to safety as the city is bombed, eventually 95% of it is destroyed. And, that same hurry takes out stained glass windows for safe storage, gets valuable icons to a new place of sanctuary. And then later the hush, the hush of walking the floor of the cathedral then littered with rubble. The hush of devastation, and in seeing the walls of the cathedral still standing, the hush of hope.

I emerge again, leaving the worshippers to their sacred duty. Outside the amplified voice of an announcer throws the names of marathon runners off the gothic façade of the cathedral. Power scooters bump their way over cobblestones. This city is running again.

This is our guide, Rolf. He told funny stories, even put on a clown nose when introducing us to the November 11 celebrations in city centre Cologne – Carnival. He also pointed out a building adornment high up on the fourth floor opposite city hall – a chubby little chap mooning the politicians. And that’s okay, on city hall another adornment depicts a head sticking its tongue out in return. Rolf wanted us to know that the people of Cologne were like that.

But he said something even more important. Members of our tour group were all from countries that comprised the Allied Forces in WWII, the Forces which bombed and destroyed 95% of his ancient city. He said that we did not fight as the enemy of the German people, but as the true friends of the German people, fighting to liberate them from the Nazi regime. He openly invited us to ask him whatever questions we might have with respect to the difficult history between our countries. He answered frankly. Then it was onto the next funny story.

But he said something even more important. Members of our tour group were all from countries that comprised the Allied Forces in WWII, the Forces which bombed and destroyed 95% of his ancient city. He said that we did not fight as the enemy of the German people, but as the true friends of the German people, fighting to liberate them from the Nazi regime. He openly invited us to ask him whatever questions we might have with respect to the difficult history between our countries. He answered frankly. Then it was onto the next funny story.

A final image of Cologne from the deck of the ship.

KINDERDIJK

How do you spell ingenuity?

I spell it k-i-n-d-e-r-d-i-j-k.

On this Grand European Cruise we have seen much grandeur. Castles, cathedrals, even a palace. We have appreciated exquisite art and heart-thrilling music. There were narrow winding streets, half-timbered houses, and ankle-twisting cobblestones. Buskers played classical music on violins, and one played a flute. We imagined the medieval folk living in ancient cities and towns. We saw present-day parents and children, dogs with humans, and we struggled to keep up with a super fit septuagenarian guide with a ribald sense of humour. We saw and dodged many bicycles. We savoured foods true to the local area. There was great beer and wine.

It all impressed me. I needed to blog to think it through, I needed to photograph it to really see.

Then we end with a tour at Kinderdijk (pronounced kinder-dike). Human ingenuity ekes out of the old wood and practical engineering. Hard work and proud but humble living spill out all over, plunging us to new depths of respect for the human spirit. A windmill is a windmill is a windmill until you climb up inside of one, see the wooden mechanisms, gingerly pick your way up the narrow steep stairs (backing your way backdown) and explore the cramped but functional quarters and where the mill family lived. Land already below river level is sinking further yet but the mills, the dikes, the ingenuity keeps it habitable and productive. Ingenious.

I’m not glad our cruise is ending, but given that it has to end, it is best that it ends here. Kinderdijk has brought us back to the humble, productive earth from the high castles, auspicious opulence, and vaulted cathedrals. It is good to be here.

I spell it k-i-n-d-e-r-d-i-j-k.

On this Grand European Cruise we have seen much grandeur. Castles, cathedrals, even a palace. We have appreciated exquisite art and heart-thrilling music. There were narrow winding streets, half-timbered houses, and ankle-twisting cobblestones. Buskers played classical music on violins, and one played a flute. We imagined the medieval folk living in ancient cities and towns. We saw present-day parents and children, dogs with humans, and we struggled to keep up with a super fit septuagenarian guide with a ribald sense of humour. We saw and dodged many bicycles. We savoured foods true to the local area. There was great beer and wine.

It all impressed me. I needed to blog to think it through, I needed to photograph it to really see.

Then we end with a tour at Kinderdijk (pronounced kinder-dike). Human ingenuity ekes out of the old wood and practical engineering. Hard work and proud but humble living spill out all over, plunging us to new depths of respect for the human spirit. A windmill is a windmill is a windmill until you climb up inside of one, see the wooden mechanisms, gingerly pick your way up the narrow steep stairs (backing your way backdown) and explore the cramped but functional quarters and where the mill family lived. Land already below river level is sinking further yet but the mills, the dikes, the ingenuity keeps it habitable and productive. Ingenious.

I’m not glad our cruise is ending, but given that it has to end, it is best that it ends here. Kinderdijk has brought us back to the humble, productive earth from the high castles, auspicious opulence, and vaulted cathedrals. It is good to be here.